Yesterday at the Old Bailey a respectable 57 year old estranged wife was given a life sentence that is the mandatory sentence when convicted of murder.

Yesterday at the Old Bailey a respectable 57 year old estranged wife was given a life sentence that is the mandatory sentence when convicted of murder.

That lady is Mrs. Frances Inglis, a nurse. The murder was that of her son, Thomas Inglis, aged 22, who lay brain damaged in hospital. Mrs. Inglis had previously been charged with attempted murder and committed the murder whilst on bail awaiting trial for the earlier offence.

This sad case has been reported on in the media and therefore the British Gazette will limit itself to reporting quoted statements and its own commentary:

Last night Thomas’s father, brothers, girlfriend and other relatives said in statement they were standing by Mrs. Inglis “100 per cent.”

Outside the court, Thomas’s brother Alexander Inglis, 27, called for a review of the way that severely disabled people’s lives can be legally ended. He said: “How can it be legal to withhold food and water, which means a slow and painful death, yet illegal to end all suffering in a quick, calm and loving way?”

Last night Detective Chief Inspector Steve Collin, the senior police officer in the case, said: “There is no such thing as mercy killing in law.” To which the British Gazette would comment that the police officer concerned should stick to catching criminals as should he wish to receive some instruction in this area of law he should read this article.

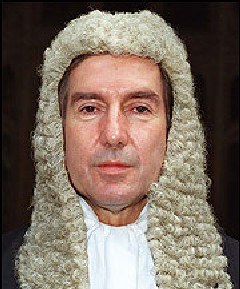

Mrs. Inglis’s trial judge was Judge Brian Barker QC, the Common Serjeant of London, the second most senior position at the Old Bailey. He told her:

“You were a devoted mother highly regarded for your work in the community…. What you did was to take upon yourself what you thought your son’s wishes would have been, to relieve him from what you described as a living hell…..But you cannot take the law into your own hands and you cannot take away life, however compelling you think the reason.”

Mrs. Inglis received a minimum term of nine years from Mr. Barker – the so called “tariff”. Mrs. Inglis has already served 423 days on remand which will be deducted from her sentence. Theoretically, she could be eligible for release on licence in seven and a half years. A word of explanation here as not all readers will be familiar with the criminal justice system.

There are two types of life sentence: mandatory and discretionary. Mandatory life sentences are given to all those persons convicted of murder. This was laid down by parliament when the death penalty was abolished in the 1960s. Up to fairly recently the Home Secretary was responsible for the release of these prisoners. Inevitably, politics intervened which helped explain why Moors Murderess the late Myra Hindley was repeatedly denied release on licence. Discretionary life sentences are applied by trial judges on defendants for a range of offences where the offender appears to be persistent.

There is often the call made in the media that “life should mean life” This is taken to mean that the person should be required to spend the rest of their natural life in prison with no prospect of release. This does happen on occasion for the most serious multiple murders. It is called a whole life tariff.

In 2002 the Lord Chief Justice, then Lord Woolf, set out guidelines for the life tariff for murder. The “starting point” for the trial judge is 15 years. To this figure years are added or subtracted depending on the aggravating or mitigating factors of the case. For the so called “mercy killing” it was set at 8 or 9 years. Readers will also recall that Mr. Martin the farmer received an initial tariff of 8 years for the murder of a burglar – not a “mercy killing”, but one where there was a substantial set of mitigating circumstances.

The British Gazette would draw its readers attention to the case of Mr Frank Lund who was convicted of murdering his wife at Liverpool Crown Court in 2007. The trial judge, Mr. Justice Silber set an extraordinarily lenient tariff of 3 years because he acted upon his wife’s request – this lady suffering very great pain from a terminal illness.

The British Gazette would also draw its readers attention to the facts that in the Martin case, Mr. Martin was found to be in the possession of an unlicensed firearm and that in the Inglis case, Mrs. Inglis’s murder weapon of choice was the class A drug heroin – acquisition, subsequent possession and use of which is illegal.

There may be many British Gazette readers who will, like the Gazette itself be pleased that Mrs. Inglis’s legal team are to lodge an appeal against both verdict and sentence. They may well speculate upon the outcome – that the Appeal Court judges, if not deciding to overturn the verdict or order a retrial might reduce the tariff by “splitting the difference” between the 9 years she received at the Old Bailey and the 3 years imposed upon Mr. Lund – meaning 6 years.

The British Gazette is not going to venture an opinion on how long Mrs. Inglis should remain in prison or if she should be in prison at all. This is because we were not at the trial and do not have full access to all the trial papers.

The British Gazette however is of the opinion that the whole practise of passing life sentences should be re-examined. Further words of explanation are required for those of us who are not practising criminal defence lawyers. When a convict who has had a life sentence (be it mandatory or discretionary) imposed upon them is released from prison they are said to be released “on licence.” This means that they can be recalled to prison should the authorities either determine that there is a risk or reoffending or that they have otherwise breached the terms of their release. A “lifer”, when released must adhere to a set of requirements. This will in all cases go beyond a simple requirement of not committing any further offences whatsoever however minor. There will be reporting requirements and possibly such as movement restrictions. These restrictions are determined by the parole board. Breach of these conditions, even very minor ones, can lead to the convict’s recall to prison.

When Mrs. Inglis is eventually released from her life sentence she too will be bound by these restrictions. The life sentence in that way is for life.

The British Gazette is of the opinion that such life sentences are very suitable for a wide variety of persistent offenders – even those convicted of non violent offences and particularly those convicted of most (but not all) sexual offences. However the British Gazette feels that to impose such a life sentence on such as Mrs. Inglis and Mr. Lund is excessive and a waste of resources. The British Gazette therefore would like to see that the mandatory sentence of life imprisonment for murder is abolished and be substituted with a discretionary life sentence. This would mean that trial judges would have open to them other sentencing options for those very rare cases such as Mrs. Inglis and Mr. Lund. Readers need not be concerned at this suggestion. In the vast majority or murder cases which are very serious, this will make no practical difference. The bank robber who shoots a member of the public dead in the course of a robbery can still expect to spend considerably more than 20 years behind bars.

Speaking the Truth unto the Nation

All very sad. I take no issue with the stance of the Gazette.