In four years time, today’s date, 1st November will make the start of a new era in British history. This is because the 1st October, 2014 will be the beginning of effective foreign rule in this country. Of course the Europhiles will say that we Eurorealists have been saying this repeatedly ever since the ink of the arch traitor Heath’s signature dried on the accession documents attached to the Treaty of Rome.

In four years time, today’s date, 1st November will make the start of a new era in British history. This is because the 1st October, 2014 will be the beginning of effective foreign rule in this country. Of course the Europhiles will say that we Eurorealists have been saying this repeatedly ever since the ink of the arch traitor Heath’s signature dried on the accession documents attached to the Treaty of Rome.

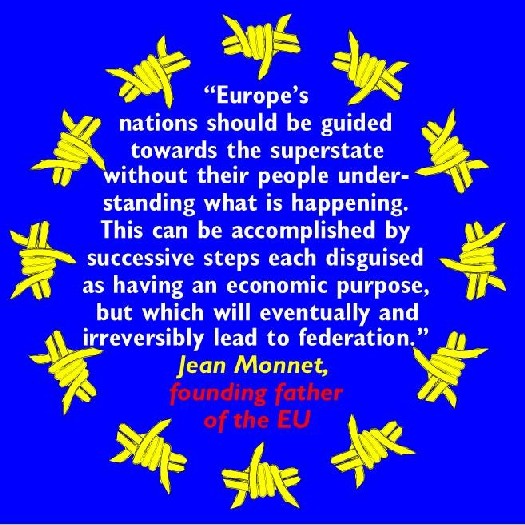

We Eurorealists have not been wrong but we may not always have precisely described the details of the “foreign rule”. The foreign rule of our country has of course been a gradual affair. British Gazette readers will know the phrase, “Slowly, slowly, catch the monkey” as obviously did Jean Monet!

What Eurorealists have been doing since before this country joined what has become the never to be sufficiently damned abomination that is the European Union, is to seek to warn the politicians and the British People of what Monet and his cronies were up to.

The reason why the 1st November, 2014 is so significant is that the European Union will by Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) be able to make laws and define policy for virtually every aspect of government policy. This will include foreign affairs and defence. That areas such as criminal justice and the police will be covered is well known. In addition the European Union will be able to extend its competences still further as the Lisbon Treaty has given it its own legal personality. This means no more need for referendums as the EU can re-invent itself at will. Chancellor Merkel already has in mind a further treaty removing all economic sovereignty from member states of the Eurozone and Olli Ilmari Rehn, European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs wants this to be extended to other member states outside the Eurozone.

The question we Eurorealists have to ask ourselves is this: What do we do about this?

There are those who suggest that we campaign and demand a referendum. Not on the Lisbon Treaty – that horse has long bolted – but on the question of the U.K. remaining a member of the E.U. In this regard we would appear to have an unusual ally – none other than Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg himself! Clegg is on record as suggesting that the “powers that be” give Eurorealists what they are demanding? Why? Because he is confident of winning the referendum is why. In this, Clegg is not likely to be wrong. The chances of we Eurorealists winning such a referendum are slight. So slight in fact that putting a £1 on the National Lottery might even be a sensible investment by comparison.

Why then should we demand a vote that we cannot win? The answer, poignantly was demonstrated bloodily on this day 96 years ago at the Battle of Coronel. This was where Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s South Atlantic Squadron engaged Vice Admiral Graf von Spee’s East Asia Squadron and suffered a heavy defeat. Outpaced and outgunned, Craddock and his men knew that they were doomed but made their gallant sacrifice knowing that in sealing their fate they also sealed the eventual fate of von Spee and his men as well.

The British Gazette suggests that we Eurorealists take a metaphorical leaf out of the late Sir Christopher’s book and engage the Europhile traitors in such a way as to mortally damage (metaphorically speaking of course) their project of keeping this former sovereign state a suzerain state of the European Union.

How? You ask.

By attacking a flank which they cannot defend. It is a basic military tactic to attack your enemy at his weakest point. We know our enemy’s weakest point. That U.K.’s membership of the European Union is unconstitutional and therefore unlawful! That each Europhile traitor who is a Privy Counsellor has committed and continues to commit the felony crime of perjury. This is because they take an oath, hand on bible, in front of their Sovereign Lady the Queen to uphold the Queen’s Majesty and ensure that no foreign prince, potentate or power shall have precedence in this land!

What the Eurorealist campaign should concentrate on is telling the British People time and time again of the lies, the perjury and the treason that has been perpetrated by these traitors. Of course there are many who will suggest that we should concentrate our fire on the dire economic consequences and the huge costs E.U. membership costs this country. That however is where the Europhile traitors will be expecting us to attack from. We know well their battle tactics: These will be to present the potential of a dire future for the U.K. were it ever to leave the E.U. This of course would include dire predictions about the country’s credit rating and the sky high debt interest we would find ourselves paying. It would include gloom laden prognostications on the flight of capital and investment from the U.K. by foreign investors, with these foreigners relocating to within the E.U. All of this would of course be given prominence by the Brussels Brainwashing Commissariat.

The BBC will of course invite Europhiles into the TV studio to debate the issue with Europhiles. They will of course seek to set the agenda of the debate and will seek to stop any Europhile from attacking on the constitutional front. They will seek to compel the Europhile representative onto the economic ground. They will want the Eurorealist in the studio to try and seek to rebut the Europhile case of doom laden disaster should we leave. Were the Eurorealist to follow this direction the end result will be a defeat as most voters faced with an absolute wall of establishment figures arguing for continued membership (which will include all three front benches of the major parties, luminaries such as Lord Sugar and Sir Richard Branson &c.) against which the BBC will invite such as Nigel Farage and Nick Griffin. Be in no doubt, the BBC will use Nick Griffin when it has to. This is because they will want to portray the Eurorealist argument as a far right extremist argument.

Instead of this what we should do is to concentrate on the constitutional argument as the Europhiles only possible counter to this is to ignore it and to change the subject. Were a Europhile ever to be so foolish as to debate whether or not they as Privy Counsellors were perjurers or that the 1688 Declaration of Rights (not the 1689 Bill of Rights) applied and overruled the European Communities Act of 1972 and inter alia, all subsequent treaties and acts, they would be entering down a road where there is only one outcome. Defeat. What our tactics should be is to keep repeating the constitutional message as each time we do it the Europhiles will run away and refuse to give battle. They will forever be obfuscating and changing the subject. This of course is something the British People will pick up on.

Below are photographs of HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth and below these an edited version of the battle’s description taken from Wikipedia.

HMS Good Hope.

HMS Monmouth.

The Royal Navy, with assistance from other Allied navies in the far east, had early in the war captured the German colonies of Kaiser-Wilhelmsland, Yap, Nauru and Samoa. Meanwhile, Vice Admiral Graf von Spee’s East Asia Squadron had abandoned its base at the German concession at Tsingtao in China following Japan entering the war on our side. Recognising the von Spee’s squadron’s potential for commerce raiding in the Pacific the Admiralty made its elimination a high priority but concentrated the search in the western Pacific after Spee’s squadron bombarded Papeete.

On 5th October 1914, the Admiralty learned from an intercepted radio communication of Spee’s plan to prey upon shipping in the crucial trading routes along the west coast of South America. Patrolling in the area at that time was Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s South Atlantic Squadron, consisting of three armoured cruisers, HMS Good Hope (Cradock’s flagship), HMS Monmouth, the modern light cruiser Glasgow, three other light cruisers, a converted liner, HMS Otranto and two other armed merchantmen. Cradock’s force was also to have been reinforced from Mediterranean waters by the newer and more powerful armoured cruiser HMS Defence, but ultimately this ship was diverted, the old battleship HMS Canopus being ordered to join him instead.

Cradock’s squadron was by no means modern, most of the crew were inexperienced with the Good Hope and Monmouth crewed mainly by reservists. Von Spee had a formidable force of five vessels, led by the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau plus a further three light cruisers, SMS Dresden, SMS Leipzig and SMS Nürnberg, all modern ships with officers handpicked by Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. Nevertheless, Cradock was ordered simply to “be prepared to meet them in company” with no effort made to clarify what action Cradock was, or was not, expected to take should he find von Spee.

On receiving his orders, Cradock asked the Admiralty for permission to split his fleet into two forces, each able to face von Spee independently. The fleets would operate on the east and west coasts of South America to counter the possibility of von Spee slipping past Cradock and raiding into the Atlantic. The Admiralty agreed and the east coast squadron, consisting of three cruisers and two armed merchantmen was formed under Rear-Admiral A. P. Stoddart.

The remaining vessels formed Cradock’s west coast squadron which was reinforced by HMS Canopus which finally arrived on the 18th October. Reprieved from its scheduled scrapping by the outbreak of war and badly in need of an overhaul, her top speed was only 12 knots. The Admiralty recognised that her slow speed meant the fleet would not be fast enough to force an engagement and also that without the Canopus the fleet stood no chance against Von Spee, so Cradock was told to use the Canopus as “a citadel around which all our cruisers in those waters could find absolute security”.

The Chief of the Admiralty War Staff, Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee, requested additional ships be sent to reinforce Cradock but this was vetoed by First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill and First Sea Lord of the Admiralty, Prince Louis of Battenberg. Cradock’s later request for HMS Defence to rejoin him was denied on the grounds that the Canopus was “sufficient reinforcement”.

On 22nd October Cradock cabled the Admiralty that he was going to round Cape Horn and was leaving the Canopus behind to escort his colliers. Admiral John Fisher replaced Battenberg as First Sea Lord on 27th October, and the following day Fisher ordered Cradock not to engage Von Spee without the Canopus. He then ordered HMS Defence to reinforce Cradock.

The previous week Cradock had sent the Glasgow to Montevideo to pick up any messages the Admiralty may have sent. Von Spee, having learned of the presence of the Glasgow off Coronel, sailed south from Valparaíso with all five warships with the intention of destroying her. The Glasgow however intercepted radio traffic from one of the German cruisers and informed Cradock who turned his fleet north to intercept the cruiser.

Given Von Spee’s superiority in speed, firepower, efficiency and numbers, Cradock knew that he would be outpaced and outgunned by von Spee. Knowing his mission was virtually impossible, Cradock decided to give battle in any event with the aim of inflicting as much damage on damage Von Spee’s squadron as he could, forcing him to use ammunition he could not replace. Ammunition which could not be used against British merchantmen. On 31 October, he ordered his squadron to adopt an attacking formation.

The same day, the Glasgow entered Coronel harbour to collect messages and news from the British consul. Also in harbour was a supply ship, Göttingen, working for the Germans, which immediately radioed with the news of the British ship entering harbour. Glasgow meanwhile was listening to radio traffic, which suggested that German warships were close. Matters were confused, because the German ships had been instructed to all use the same call sign, that of Leipzig. Von Spee decided to move his ships to Coronel, to trap Glasgow, while Admiral Cradock hurried north to catch Leipzig. Neither side realised the other’s main force was nearby.

At 9:15 on the morning of 1st November, the Glasgow left port to meet Cradock at noon, 40 miles west of Coronel. Seas were stormy so that it was impossible to send a boat between the ships to deliver the messages, which had to be transferred on a line floated in the sea. At 1:50 that afternoon the ships formed into a line of battle fifteen miles apart and started to steam north at 10 knots searching for Leipzig. At 4:17 pm Leipzig, accompanied by the other German ships, spotted smoke from the our line. Von Spee ordered full speed so that Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Leipzig were approaching the us at 20 knots, with the slower light cruisers Dresden and Nürnberg some way behind.

At 4:20 pm Glasgow and Otranto saw smoke to the north, and then three ships at a range of twelve miles. Our ships reversed direction, so that both fleets were moving south, and a chase began which lasted 90 minutes. Cradock was faced with a choice, either to take his three cruisers capable of twenty knots, abandon Otranto and run from the Germans, or stay and fight with Otranto which could only manage sixteen knots. Von Spee’s ships slowed at a range of 15,000 yards to reorganise themselves for best positions, and to await best visibility, when our ships were to their west would be outlined against the setting sun.

At 5:10 pm Cradock decided he must fight, and drew our ships closer together. He changed course to south-east and attempted to close upon the German ships while the sun remained high. Von Spee declined to engage and turned his faster ships away, maintaining the distance between the forces which sailed roughly parallel at a distance of 14,000 yards. At 6:18 Cradock again attempted to close, steering directly towards the enemy, which once again turned away to a greater range of 18,000 yards. At 6:50 pm the sun set; Von Spee closed to 12,000 yards and commenced firing.

Von Spee’s ships had sixteen 8.2-inch guns of comparable range to the two 9.2 inch guns on Good Hope. One of these was hit within five minutes of the engagement starting. Of the remaining 6 inch guns on our ships, most were in casemates along the sides of the ships, which continually flooded if the gun doors were opened to fire in heavy seas. The merchant cruiser Otranto, having only 4 inch guns and being a much larger target than the other ships, retired west at full speed.

With our 6 inch guns having insufficient range to match the German 8.2 inch, Cradock attempted to close on the German ships. By 7:30 he had reached 6,000 yards, but as he closed the German fire became correspondingly more accurate. Both Good Hope and Monmouth were on fire, presenting easy targets to the German gunners now that darkness had fallen, whereas the German ships had disappeared into the dark. Monmouth was first to be silenced. Good Hope continued firing, continuing to close on the German ships and receiving more and more fire. By 7:50 pm she had also ceased firing; subsequently her forward section exploded, then she broke apart and sank, with no one actually witnessing the sinking.

Scharnhorst switched firing towards Monmouth, while Gneisenau joined Leipzig and Dresden which had been engaging Glasgow. The German light cruisers had only 4.1 inch guns, which had left Glasgow relatively unscathed, but these were now joined by the 8.2 inch guns of Gneisenau. John Luce, captain of the Glasgow, determined that nothing was to be gained by staying and attempting to fight. It was noticed that each time he fired, the flash of his guns was used by the Germans to aim a new salvo, so he also ceased firing. One compartment of the ship was flooded, but she could still manage 24 knots. He returned first to Monmouth, which was now dark but still afloat. Nothing was to be done for the ship, which was sinking slowly but would attempt to beach on the Chilean coast. Glasgow turned south and departed.

There was some confusion amongst the German ships as to the fate of the two armoured cruisers, which had disappeared into the dark once they ceased firing, and a hunt began. Leipzig saw something burning, but on approaching found only wreckage. Nürnberg, slower than the other German ships, arrived late at the battle and sighted Monmouth, listing and badly damaged but still moving. After pointedly directing his searchlights at the ship’s ensign, an invitation to surrender—which was declined—he opened fire, finally sinking the ship. Without firm information, von Spee decided that Good Hope had escaped and called off the search at 10:15 pm. Mindful of the reports that a Royal Navy battleship was around somewhere, he turned north.

With no survivors from either Good Hope or Monmouth, 1,600 officers and men of the Royal Navy were dead with Cradock among them. Glasgow and Otranto both escaped (the former suffering five hits and five wounded men). Just two shells had struck Scharnhorst, neither of which exploded: one 6 inch shell hit above the armour belt and penetrated to a storeroom where, in von Spee’s words, “the creature just lay there as a kind of greeting.” Another struck a funnel. In return Scharnhorst had managed at least 35 hits on Good Hope, but at the expense of 422 8.2 inch shells, leaving her with 350. Four shells had struck Gneisenau, one of which nearly flooded the officers’ wardroom. A shell from Glasgow struck her after turret and temporarily knocked it out. Three of Gneisenau’s men were wounded; she expended 244 of her shells and had 528 left.

Von Spee afterwards commented on the Cradock’s tactics. He had been misinformed that the battleship Canopus sighted in the area was a relatively modern Queen-class ship, whereas it was a similar appearing, old and barely seaworthy Canopus class battleship, but nonetheless had four 12 inch guns and ten 6 inch. Von Spee believed he would have lost the engagement had all the British ships been together. Despite his victory he was pessimistic of the real harm done to the Royal Navy, and also of his own chances of survival. Cradock had been less convinced of the value of the Canopus, being too slow at 12 knots to allow his other ships freedom of movement and manned only by inexperienced reservists.

The official explanation of the defeat as presented to the House of Commons by Winston Churchill stated: “feeling he could not bring the enemy immediately to action as long as he kept with Canopus, he decided to attack them with his fast ships alone, in the belief that even if he himself were destroyed… he would inflict damage on them which …would lead to their certain subsequent destruction.”

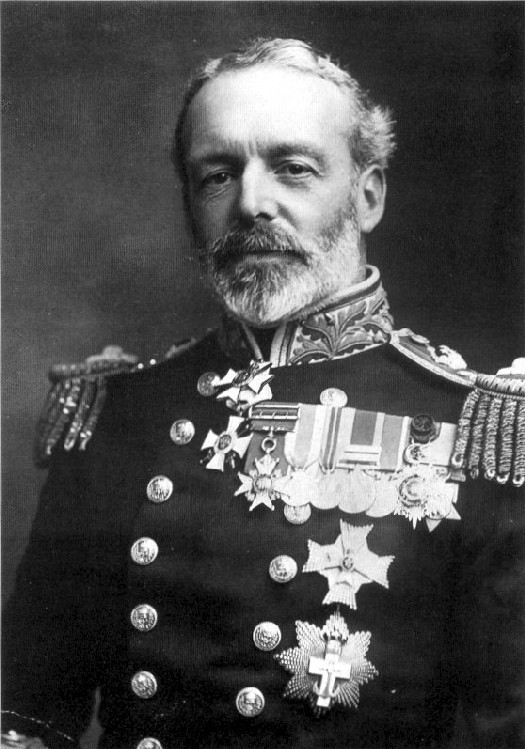

On 3rd November, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nürnberg entered Valparaiso harbour and were welcomed as heroes by the German population. Von Spee refused to join in the celebrations: presented with a bunch of flowers he commented, “these will do nicely for my grave”. He was to die with most of the men on his ships approximately one month later at the Battle of the Falkland Islands, on 8 December 1914. A monument to Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock (above) was erected in York Minster. It is on the east side of the North Transept towards the Chapter House entrance. There is also a monument to Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock in the graveyard at All Saints church Catherington in Hampshire.

A monument to Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock (above) was erected in York Minster. It is on the east side of the North Transept towards the Chapter House entrance. There is also a monument to Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock in the graveyard at All Saints church Catherington in Hampshire.

David Cameron used criminal deception to become Prime Minister, using the promise of a referendum on alllowing the EU any expansion of power over the UK.

Following his ludricous decision to expand expenditure on Foreign Aid, while stripping the aircraft carriers of their aircraft, I wrote: “If there is not a plot afoot, whereby the EU comes to our rescue and offers to take command of one of our new carriers; then I would paint my face, buy a red nose and take up clowning.

Low and behold just two days after getting nowhere with his demand of a freeze on the EU budget, he’s signing away our armed forces to the EU.

Do not forget that France is the junior partner in the Franco/German Accord, and it will be Angela Merkel Calling the shots.

As for a referendum on leaving the EU, we have little time to achieve it, as withdrawal from the EU is also included in the 1st November 2014’s list of policy that will be decided by QMV.